Celebrating freedoms, fighting for equality

Juneteenth — short for “June Nineteenth” — is an annual holiday in African American communities that commemorates the symbolic end of slavery in Texas. Also known as Emancipation Day, Freedom Day, Jubilee Day or Liberation Day, Juneteenth is observed primarily in local celebrations nationwide and also serves as an occasion to reflect on social, political, cultural, and economic progress of African Americans.

HISTORY

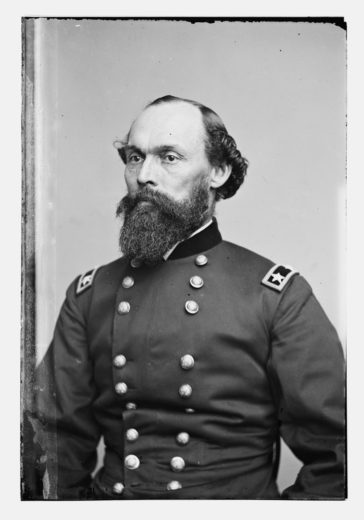

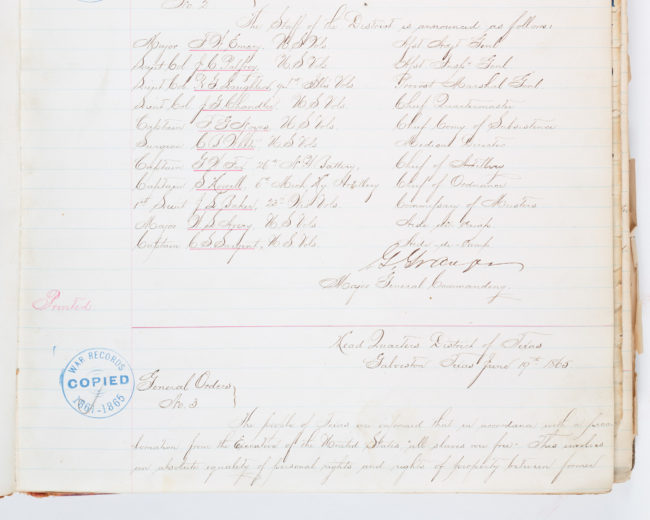

On June 19, 1865 — some two months after Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, Virginia, effectively ending the Civil War — Union general Gordon Granger arrived at U.S. Army headquarters in Galveston, Texas and read General Order No. 3, which states:

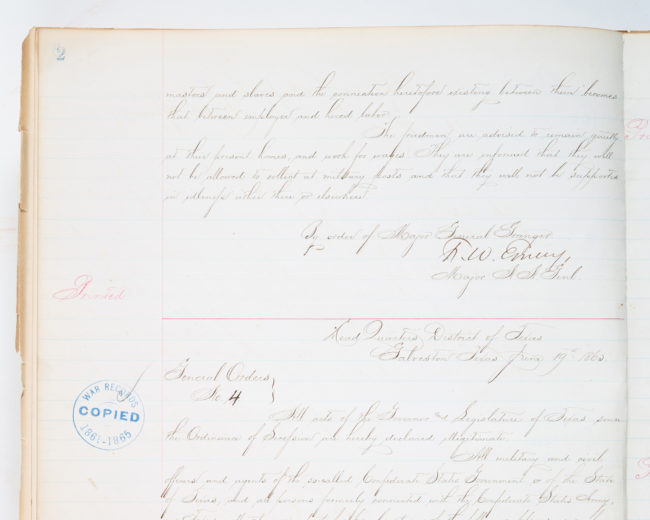

The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.”

Gen. Granger’s order referenced the Emancipation Proclamation, penned by Abraham Lincoln on September 22, 1862, that freed enslaved people in the states and counties “in rebellion” during the Civil War. Slavery was still legal in Missouri, Kansas, Kentucky, Tennessee, Maryland, Delaware, and parts of Louisiana.

While its purpose was to gain military advantage and its scope was limited, the Emancipation Proclamation shaped a new sense of justice and moral imperative for the country. Even though the proclamation took effect January 1, 1863, emancipation was enforced gradually as the Union Army advanced. It took nearly three years for the news of the proclamation, and freedom, to reach Texas.

While the order guaranteed freedom and affirmed equality between “masters and slaves,” the prejudicial language in the last sentences signaled that the fight for equality would continue. In fact, the enslaved in Delaware and Kentucky were not freed until the passage of the 13th Amendment in December, 1865. Two Texas Supreme Court rulings in 1868 and 1874 finally gave legal status to freed African Americans.

CELEBRATIONS

In Texas, African Americans gathered as soon as 1866 to celebrate their freedom. In Houston, newly freed African Americans settled in Freedman’s Town (now 4th Ward) among other locales, building homes, churches, schools and businesses. By 1872, local leaders raised funds to purchase a ten acre tract of land east of Downtown (Emancipation Park) to celebrate Juneteenth. Houston’s annual celebrations drew thousands.

Juneteenth celebrations spread across the South and eventually all over the nation as African Americans migrated north and west to pursue economic opportunities and to flee the injustices of segregation.

Texas was the first state to recognize Juneteenth as a state holiday in 1979; currently all states but Hawaii and North and South Dakota observe or commemorate the day. Juneteenth became a national federal holiday June 17, 2021. Modern celebrations include street fairs, parades, rodeos, cookouts, family reunions, historical reenactments, and Miss Juneteenth contests.

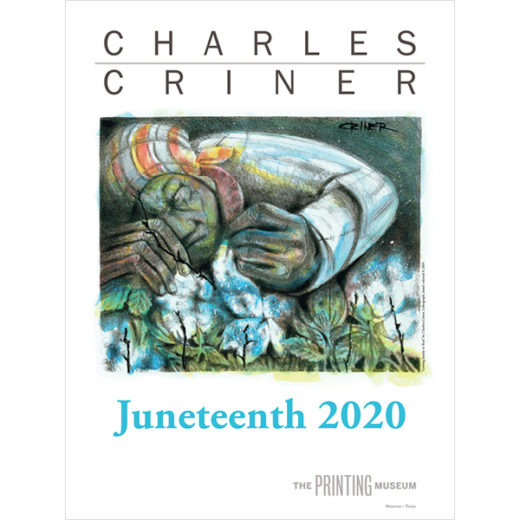

The Museum has celebrated Juneteenth for nearly two decades by producing Juneteenth posters, based on works by Master Printer Charles Criner, with a gracious multi-year sponsorship from Heidelberg USA. Each poster evokes the spirit of Juneteenth and conveys the continued significance of this momentous event in American history.